They say all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy… And here at the AMPLab, we do occasionally take a break from our day jobs and have some fun. For instance, when I’m not obsessing over our build system, I obsess over cars. Not only do I have a massive toolbox on wheels with a wrench for every occasion, I also provide racetrack instruction and am building a car that will soon be competing in NASA Time Trial events.

Over the last several years, as described in this article, racing cars has become a popular pastime among the Silicon Valley tech crowd. I discovered track events and racing almost seven years ago, but instead of the high-powered board room meeting track events, I specialize in my own special kind of grassroots obsession. An obsession that somehow combines cars, racing, data and open source.

It’s endurance racing… And not just any kind of endurance racing, but crapcan racing for $500 cars in The 24 Hours of Lemons. The idea behind Lemons is to keep costs down and make endurance racing something that anyone with the desire to do it an attainable and (mostly) affordable hobby. Started in 2007, the series has grown from one race in California to being a national series with over 40 races per year.

It’s important to note that the $500 limit applies only to the car, and you can sell off things like the interior to bring the total spent to $500… Got some nice OEM seats? A decent interior? Strip it out and sell it! Safety equipment, on the other hand, like the racing seat and cage doesn’t count towards the total. Neither do brakes, wheels, tires and “driver comfort” items (fancy steering wheel, driver cooling and hydration systems, etc). All in all, a decent build will cost roughly $5000-$8000 when all is said and done. To put this in perspective, this is less than a THIRD of the cost of a competitive and race-prepped Spec Miata, and that figure skyrockets if you want to race something like a Porsche.

The fields are huge (180+ cars racing at once) and the variety of vehicles is staggering (including a 1961 Rambler American, lots of BMW E30s, various 1980s econoboxes, and the occasional Geo Metro powered by a rear-mounted Honda CBR motorcycle engine). Theme is important, and some of these cars would make excellent Burning Man art cars. You can read more about some of the crazier builds here… It’s amazing what people put on the track, and how well some of them do. Watching the race itself is a spectacle.

With cars like this, built by teams in their backyards, or even in fully stocked professional race shops, things are bound to go south. In fact, this is so common, and teams scramble and help each other rebuilding and swapping engines overnight hoping to get back in to the race, that there’s even an award for this: The Heroic Fix. Some other awards are the “Index of Effluency”, “Organizers Choice”, “We Don’t Hate You, You Just Suck”, as well as the smallest (physical sized) trophies for the overall winners in the three classes (A, B and C, extremely loose categories based on the descending chance of either winning overall or just finishing the race). It’s all a bit tongue-in-cheek, and meant to keep things from getting too serious. All of us out there want to have fun, but without being overly competitive. Cheating is expected, and bribes for the judges (usually booze) are plentiful. The grassroots community is amazing, and it’s the reason Lemons is so successful.

But, even though it’s friendly, the races are extraordinarily competitive. The top teams use every trick possible to get an edge. We, like many other teams, use data.

My team, Captained by Chris More, runs a 1991 Mazda RX-7. Our car is themed as a U-Haul truck, and the twist echoes the common sentiment that many people have when renting a nearly broken down box truck or sketchy trailer for a move: FU-Haul

Unlike some of the junkers on the track, we’ve spent a lot of time making the car fast, reliable and competitive. That being said, over the course of a race (usually 16 hours, split over two days), things that one wouldn’t expect to fail do, and sometimes in spectacular fashion. In our most recent race (Sears Pointless, March 20-21 2015 at Sonoma Raceway), our transmission decided to spray it’s vital juices up through the gear shift gate and cover the entire interior of the car (including the driver) with a coating of smelly transmission fluid. Our front brake rotors were extremely warped as well, and under heavy braking (the best kind), the steering wheel would jerk from side to side and almost be ripped from our grasp. Not to mention the severe fuel cutoff issues when we were below half a tank of gas… Thankfully, we were able to hold it together and finish the race. We placed 11th out of 181 entries, nearly cracking the top 10!

But what does this have to do with big data and open source?

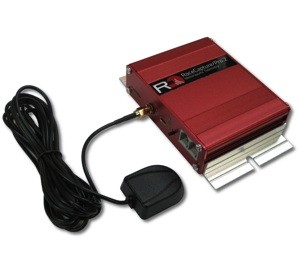

The four team members are all involved in high tech, consisting of Mozilla, Level 3 and Google alums. We are all about open source, and love data… And we collect in-car telemetry data with an open source hard- and software product from Autosport Labs called Race Capture Pro.

While we don’t use Spark for data processing (go go Google Sheets!), the data we collect is invaluable for helping us keep track of how the car and drivers perform during the race, as well as post-race bragging rights for who turned the fastest average lap (sadly, it wasn’t me). With this data we were able to analyze things like our average pit stop time (~5 minutes, 30 seconds over 6 stops), each driver’s average lap time in traffic (Chris is the best), and with an open track (all four of us were within .6 seconds average over the entire weekend when turning fast laps, which is kind of amazing).

These metrics show that everyone except for Chris needs to improve their race traffic management skills, and that we need to bring our pit stop times down to at least 5 minutes to contend for a top-5 finish. Our lap times are consistent and competitive, proven with data, and we know that the drivers and car are capable of more.

For a taste of how cool this data and product is, check out our statistics from the race.

For some fun reading, here’s a preview of the most recent race, and then coverage of the results.

And finally, here is some on-track action during my two hour long stint on the first day of racing… Enjoy the wonderful sound of a rotary engine spinning up to nearly 9000rpm!